Advertisers Awaken to Blindness: Audio Description in Advertising

George Wurtzel is blind. But that doesn’t stop him from teaching woodworking at Lighthouse San Francisco and Enchanted Hills Camp for the Blind. And why should it?

“Just because you can’t do it doesn’t mean that I can’t do it,” laughs George. “I can’t run a four-minute mile. There are some people who can, but don’t tell me that I can’t do it. Give me the tools. Give me the opportunities. Give me the education. Give me the accommodation that I need and let me try and fail on my own.”

“I was a huge cross-country skier for years, and years, and years,” George recalled during a 2018 episode of The Interactive Accessibility Podcast. “I skied a cross-country ski race in Northern Michigan one time, the White Pine Stampede, the very first year they ever had it. Almost 50 years ago, now it may be 50 years ago. There was 250 people that started that race. I finished number 43 in that race. I was the last person to finish.”

But finish he did. “They were pretty amazed that a blind guy finished the race. I said, ‘You know, it was blizzard conditions most of the time. You couldn’t see anyway!’” That’s just the way Wurtzel looks at life.

Blindness wasn’t the only thing that qualified George to star in Subaru’s first audio-described television commercial, “See the World.”

“The casting call said, ‘Looking for a blind man aged 50 to 70, a little bit rustic, and a little bit curmudgeonly.’ I think that it’s the age thing that got me in, but I’m not sure,” he jokes, adding, “I certainly fit the category of rustic. My standard attire for working in my industry for the last 30 years has been a pair of bib overalls and a flannel shirt, which is pretty much my costume of choice. I got a long beard, shaggy hair, live on top of a mountain, and I’m a little grumpy.”

If he is grumpy, it certainly doesn’t come through in the commercial. Instead, he comes across as a kindly, intuitive man who sees what those of us with vision do not, as he volunteers to guide a sighted couple looking for ‘the Peninsula Trail.’ “Peninsula Trail. You won’t find that on a map. I’ll take you there,” George’s character says, as they follow him to their Subaru Outback. Amazingly, he navigates the roads with ease, and the three end up in the woods, where he skillfully navigates terrain his counterparts find challenging. Finally, on a bluff overlooking the ocean, he stretches out his arms and says, “If you listen real hard, you can hear the whales.”

Not the First

Subaru was not the first major advertiser to run an audio-described TV commercial. That honor goes to Proctor & Gamble. In late 2017, P&G was named Inclusive Service Provider of the Year for producing the first audio-described ads ever aired in the United Kingdom – a 30-second spot for Fairy dishwashing detergent, which had aired in August.

P&G’s Inclusive Design Consultant Sam Latif explains the company’s motivation: “We recognise it’s the everyday interactions that make the biggest difference to making people feel valued and included and it’s also a business opportunity as our message now is expanding to 2 million consumers who have vision loss in the UK with whom we are able to now better communicate.”

Months earlier, Sam sat quiet in a meeting while her co-workers laughed at Britain’s now-iconic ‘Flash the Singing Dog’ commercial (not originally audio-described). Herself vision-impaired, Sam couldn’t understand what was so funny about the commercial, until her sighted coworkers explained it was the dog who was singing.

Sam is now the Global Leader of P&G’s People with Disabilities Network. A playlist of 18 P&G audio-described ads can be found on YouTube.

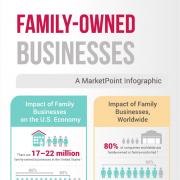

Market Motives

The business case for inclusive advertising is easily made. According to the National Federation of the Blind, as of 2015, more than 7.3 million U.S. citizens were reported to have a vision disability. That was 2.3 percent of the total population. Among those 16 years of age and older, those with vision disabilities rose to 2.7 percent of the population, and above age 64 the number shoots to 6.4 percent.

African Americans are at least 25 percent more likely than Whites to suffer vision impairment, and Alaskan Natives and Native Americans 74 percent more likely than Whites.

These numbers comprise a large segment of the consumer market.

Definition, Adoption, and Regulation

The American Council of the Blind describes audio description (AD) as “narration added to the soundtrack to describe important visual details that cannot be understood from the main soundtrack alone… Audio description of video provides information about actions, characters, scene changes, on-screen text, and other visual content.” Producers of audio description (also known as “video description” or “descriptive narration”) usually add their context during existing pauses in dialogue.

In February 2018, the New York Times reported Amazon Prime Video “had about 350 movies and TV shows with audio descriptions, including ‘The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel’ and a number of popular theatrical films.” Some streaming and broadcast providers, including Apple’s iTunes Store, also make audio-described shows available for purchase or rental. The Netflix original series “House of Cards” headlines their offerings, which include over 500 documentaries, original programming and children’s shows. The American Council of the Bind website features a broad list of streaming services with “added narration about scenes, characters, costumes and more — for people who cannot see what is happening.”

Will Schell, a blind attorney with the Disability Rights Office of the Federal Communications Commission, reports that as of July 1, 2018, Federal regulations require stations to provide 87.5 hours of audio-described programming per quarter – or about 7 hours per week – 50 hours of which must be aired during prime time. These regulations do not apply to advertisements, live programming, or near-live programming. “As far as I know, I don’t think there’s anyone who’s describing the commercials in between the actual show, or the other content that pops up in between shows. So, it’s really just for the show itself.”

Schell was talking, of course, about the broadcasters not providing described content – not the advertisers themselves.

A Personal Observation

My first exposure to audio-described advertisements was the Subaru ad featuring George Wetzel, which delighted me for its ingenuity. Was I witnessing a new period of advertising inclusivity, in which challenged individuals were portrayed with empathy, while viewers were awakened to the vision-impaired world of audio description?

At the time, I was unaware the audio-described-ad game had been kicked off a year earlier by Proctor & Gamble. Coincidentally, my second exposure to audio description was a P&G ad, “Chopsticks,” in which a young boy learning to eat with chopsticks drops his dumpling, tipping and spilling his bowl. In slow motion, the dumpling slides across the glass tabletop and into the waiting mouth of the family dog. “Cute,” I thought, “but lacking the empathy evident in George Wurtzel’s Subaru ad.”

Audio Description can be a confusing thing. One viewer wrote PBS, asking, “A narrator is describing everything that happens on the shows I am watching. How do I make it stop?” The help center explained he had accidentally activated his television’s “Descriptive Video Service (DVS) option, a service broadcast on a Second Audio Program (SAP) which provides enriched verbal descriptions of what is heard and seen on a TV’s primary audio and video channels.” An easy mistake. But the sentiment must be shared by many who see their first audio-described ad.

Ironically, “what did we do wrong” may be the most appropriate and enlightened response to AD. What did we do wrong, all these years, by not offering audio description for the visually impaired? And how quickly can we fix it? What can we do, right now, to make all programming more accessible? How can we tear down the social barriers that keep so many of us in the dark about living blind? What other human challenges can be addressed by raising awareness and sensitivity through communication channels we take for granted every day? What else do we, as blithely self-absorbed consumers and marketers, need to awaken to?

Yes. What, indeed?